Capital Losses: Rules to Know for Tax Loss Harvesting

Tax loss harvesting requires an understanding of the capital loss rules for deductions, carryovers, and more.

I spend a lot of my day advising clients on how they can reduce their capital gains tax using the qualified opportunity zone program, which relies on investors having capital gains to invest. With the recent tumult in the market, capital gains are harder to come by, and this is making fundraising for the program more difficult. But a down market, where capital losses can be more common than capital gains, presents other tax opportunities – capital losses can be used to offset capital gains, can be carried forward, and can offset a limited amount of ordinary income like wages.

Whether you sell investment assets with a view toward tax planning or for other reasons, you need to know how your capital losses will be treated. Below is a brief overview of the relevant rules that will help you strategically harvest your losses, including technical topics like netting and calculation of capital loss carryforwards. As you navigate the uncertainties of this down market, having a grasp on the relevant tax rules may help you find opportunities to use the down market to your advantage when tax season comes around.

Capital Losses in General

Generally, a capital loss is a "realized" loss from the sale or exchange of a capital asset, such as investment property like stocks, bonds and cryptocurrency. If you held your capital asset for one year or less before the sale or exchange, your loss is generally short-term capital loss. On the other hand, if you held your capital asset for more than one year before the sale or exchange, your loss is generally long-term capital loss. As discussed below, this distinction is important when determining how to deduct and carryover capital losses.

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free E-Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

Other types of events besides sales can also give rise to a "realization." For instance, property that is involuntarily converted or taken by the government, or over which you grant an exclusive use right to others, may be treated as sold. A capital loss may also be realized when a security becomes worthless or is abandoned. Losses on sales or exchanges of property between related parties (i.e., spouses, siblings, parent, grandparents, children, etc.) are suspended until there is a sale to a third-party (and then the seller gets to take the loss rather than the original family member).

Capital Loss from Worthless Securities

You may deduct a loss for worthless stock or securities (including stocks and bonds) in the tax year in which the security becomes totally worthless, as opposed to merely declining in value. If the security is otherwise held as a capital asset (i.e., for investment purposes) the loss will be a capital loss.

Because the loss may only be claimed in the tax year in which the security becomes totally worthless, you should keep records documenting the event that resulted in complete worthlessness of your security. If you abandon your securities this may be an event that results in complete worthlessness (but again, proper recordkeeping is essential!).

If you own securities that become worthless during the year, your loss is deemed realized on the last day of the taxable year for purposes of determining your holding period.

Deducting Capital Losses

When calculating the tax owed (if any) when you sell or exchange a capital asset, you can generally deduct losses from the sale of your capital assets to the extent of your capital gains. However, you have to follow certain "netting rules" to calculate the proper deduction. If you have a net capital loss after following the netting rules, you can then deduct up to $3,000 ($1,500 if married filing separately) from your wages, taxable retirement income, and other ordinary income.

Caution: Except in the case of certain limited casualty events, losses from the sale of personal use property such as a car, house, or home furnishings can't be deducted.

Netting Rules. If you have a mix of short- and long-term capital gains and losses, you need to understand the order in which losses offset gains. First, short-term losses are used to offset short-term gains, and long-term losses are used to offset long-term gains. Then, if there are any losses remaining, they can be used to offset the opposite type of gain.

Your capital losses for the year also include any loss carryforwards you have from previous years (you can't elect not to use these). For example, assume you have the following in the same year:

- $250 short-term loss;

- $300 short-term gain;

- $1,000 long-term loss; and

- $990 long-term gain.

First, you must offset the $250 short-term loss against the $300 short-term gain, which results in a net short-term gain of $50. Then you must offset the $1,000 long-term loss against the $990 long-term gain. That leaves you with a net long-term loss of $10. In this case, your $10 long-term loss can be used against your $50 short-term gain, and you'll pay tax on $40 at the short-term capital gains tax rates (which are the same as the tax rates you pay on wages and other ordinary income).

If you understand the netting rules, you can be more strategic in determining which capital assets to sell (or not sell) when you rebalance your portfolio. For example, if you had an additional $40 of loss (whether long- or short-term), it could be used to completely offset any capital gain in the example above. Or, if it looks like you'll have excess short-term capital losses, you might not want to trigger any additional long-term capital gain to offset it that year. Since short-term capital gains and ordinary income are taxed at higher rates than long-term capital gains, it might be better to carryover the short-term capital loss and use it to offset expected short-term capital gain or ordinary income next year.

Deduction Against Ordinary Income. If you have a net capital loss, you can deduct up to $3,000 of it against ordinary income like wages ($1,500 for married individuals filings separately). The $3,000 limit applies to both your current year capital losses and your capital loss carryforwards from prior years. Also, the $3,000 is treated as short-term capital gain for purposes of determining your carryforwards (see example below).

Tax Tip: Losses from the sale of certain small business corporation stock (i.e., up to $1 million of common stock of a company meeting a 50% gross receipts test limiting its passive income) are ordinary losses, not capital losses. As a result, they can generally be used to offset ordinary income up to a limit of $100,000 if you're married and file jointly, or $50,000 otherwise.

If you have capital losses in excess of what you can use this year to offset your capital gains and the $3,000 limit on offsetting ordinary income, you can carry forward your excess capital losses to future tax years until they are completely used.

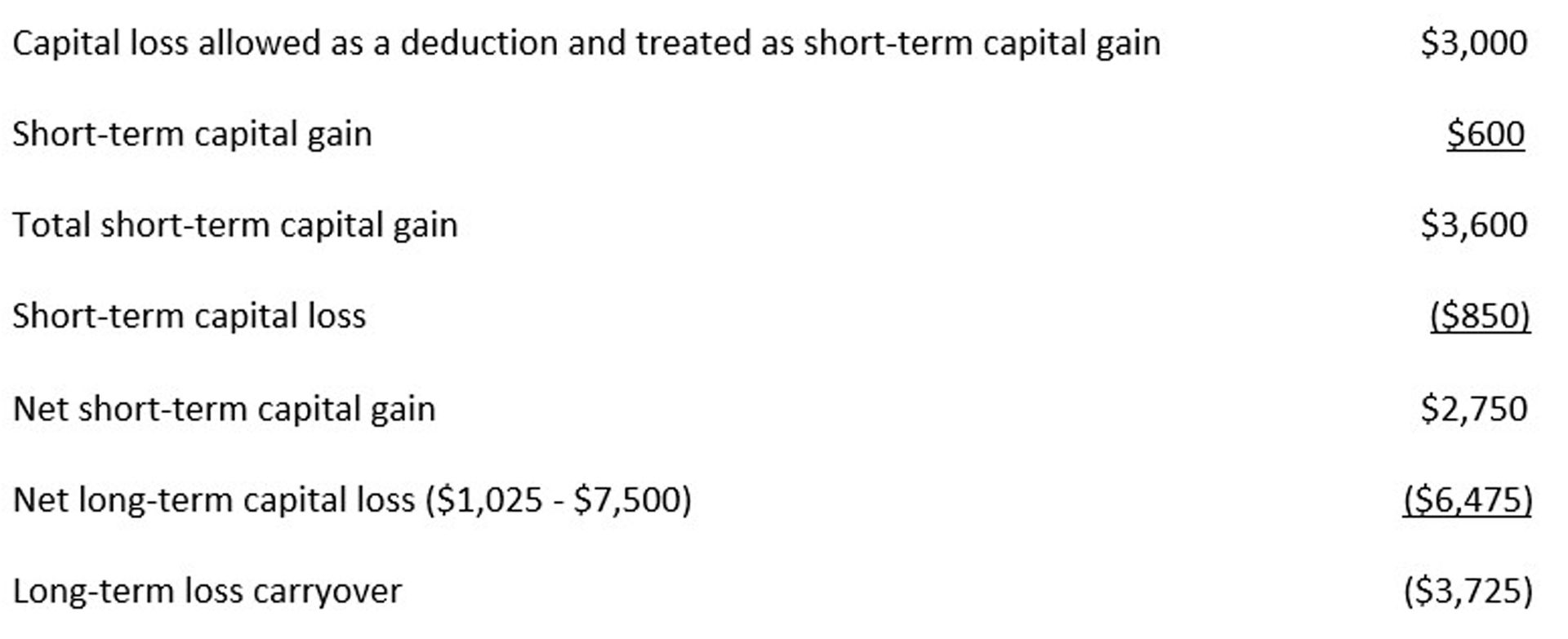

For example, assume you have the following in a year:

- $40,000 ordinary income;

- $600 short-term capital gain;

- $850 short-term capital loss;

- $1,025 long-term capital gain; and

- $7,500 long-term capital loss.

You can offset a total of $1,625 of capital losses against your capital gains. Plus, $3,000 of your excess net capital loss is also deductible against your ordinary income. The $3,000 deduction uses up your net short-term capital loss of $250 ($850 - $600) and $2,750 of your net long-term capital loss, resulting in a balance of $3,725 ($7,500 - $1,025 - $2,750) in long-term capital loss available for carryover to the next year. The computation of the carryforward is as follows:

Put differently, the excess of net short-term capital losses over net long-term capital gains for the tax year is a short-term capital loss in the next year, while the excess of net long-term capital losses over net short-term capital gains for the tax year is a long-term capital loss in the next year.

You can't carry back your capital losses to prior tax years.

Tax Loss Harvesting

Now that we've covered the basics, what tax planning can you do to take advantage of these rules? That's where "tax loss harvesting" comes into the picture.

Tax loss harvesting is a strategy to sell stocks or other investment assets that have declined in value for the specific purpose of generating capital losses. You can harvest tax losses if you have taxable capital gains that you want to offset, to take advantage of the $3,000 deduction against ordinary income, or to generate carryforwards to use in a future tax year.

Although it may seem counterintuitive to sell an asset that has declined in value (and recognizing a true economic loss) rather than waiting for the value to recover, in the case of stocks it may be possible to replace the investment with something that serves the same basic purpose in your investment portfolio (e.g., you sell a single name technology stock and replace it with a technology index fund). But note that the "wash sale" rule prevents you from using a loss for tax purposes if you repurchase the same or substantially identical securities within 30 days before or after your sale, or enter into a contract to acquire such stock or securities. Ordinarily, stock of one company isn't considered substantially identical to stock of another company for purposes of the wash sale rule.

Here are a few other tips that may help you with tax loss harvesting:

- In general, you probably don't want to harvest losses if you're not subject to tax on your capital gains – whether that's because you're in the 0% bracket for long-term capital gains this year, or because you already are in a net taxable loss position. For 2022, the 0% rate applies to long-term capital gains of taxpayers with taxable incomes up to $83,350 for joint filers, $55,800 for head-of-household filers, and $41,675 for single filers and married couples filing separate returns. Note that the brackets refer to taxable income, so you may still benefit from the 0% rate if your adjusted gross income is higher than the above thresholds. You may also qualify for some benefit from the 0% rate even if your total taxable income exceeds the above thresholds – for example, if all of your taxable income is capital gain and qualified dividend income.

- Be cognizant of timing. Sell assets before the end of the year if your goal is to use losses in the current taxable year and know when your prior gains and losses were realized. Know how much short- and long-term gain and loss you're starting with, respectively, including any carryforwards.

- If you harvest tax losses, make sure to sell securities out of your taxable investment accounts. Generating tax losses in retirement accounts won't help you, since gains and losses in those accounts aren't generally included on your personal tax return. (For Roth IRAs, you may be able to include a loss if the account has been fully distributed and the total distributions are less than your basis in the account.)

- Pay attention to the netting rules. For example, if you already have capital gains (assuming you're taxed in a higher bracket), sell assets to generate offsetting capital loss. But avoid using long-term capital losses to offset long-term capital gains. Instead, consider saving those to offset short-term capital gain or ordinary income, subject to the $3,000 limit. Also, if you already have more than $3,000 in capital losses, take capital gains (preferably short-term) to absorb the excess. And take capital losses in years when you have short-term gains (which are taxed at higher rates).

Reporting Requirements

When you file your annual tax return, you may have to complete some additional forms if you had a capital loss during the tax year. Report your transactions giving rise to capital loss on Form 8949. This includes capital losses you earn through investments in mutual funds and other investment vehicles, as reported to you on 1099 or K-1 forms. Attach Form 8949 to your Form 1040.

Calculate your net capital gain or loss and report capital loss carryforwards from any prior year on Schedule D. You also must attach Schedule D to your tax return.

-

The Clock Is Ticking on Tax Cuts: Act Now to Avoid Missing Out

The Clock Is Ticking on Tax Cuts: Act Now to Avoid Missing OutEstate and gift tax exemptions are at an all-time high until the end of 2025. That may seem like a long way off, but setting things up could take longer than expected.

By Christopher F. Tate, J.D. Published

-

Ready for a Career Checkup? Five Steps to Plan What’s Next

Ready for a Career Checkup? Five Steps to Plan What’s NextAsking yourself some pointed questions to figure out what you want and what you’re good at can bring more purpose and fulfillment to your professional life.

By Anne deBruin Sample, CEO Published

-

Types of Income the IRS Doesn't Tax

Types of Income the IRS Doesn't TaxIncome Tax It may feel like the IRS taxes most of your hard-earned money, but some types of income are nontaxable.

By Kelley R. Taylor Last updated

-

Why You’ll Still Pay Oklahoma Grocery Tax

Why You’ll Still Pay Oklahoma Grocery TaxState Tax Oklahoma is eliminating state grocery taxes, but that doesn’t mean groceries will be tax-free.

By Katelyn Washington Last updated

-

Last-Minute Tax Savings Guide for 2023

Last-Minute Tax Savings Guide for 2023Tax Savings April 15 is weeks away, so it's not too late to save your 2023 taxes.

By Sandra Block Published

-

Why You Should Care About Your 2026 Taxes Now

Why You Should Care About Your 2026 Taxes NowTax Planning It's not to early to prepare for the possibility that your taxes will go up in 2026.

By Sandra Block Published

-

Capital Gains Tax Exclusion for Homeowners: What to Know

Capital Gains Tax Exclusion for Homeowners: What to KnowTax Breaks The IRS capital gains home sale exclusion can be a valuable tax-saving tool if you’re eligible.

By Kelley R. Taylor Last updated

-

Save During Alabama’s Severe Weather Preparedness Tax Holiday

Save During Alabama’s Severe Weather Preparedness Tax HolidaySales Tax Holiday Certain items will be tax-free during the Alabama severe weather preparedness sales tax holiday this year, but there are specific rules to follow.

By Katelyn Washington Last updated

-

Will Your IRS Refund Be Less This Year?

Will Your IRS Refund Be Less This Year?Tax Refunds Data show federal tax refunds are lower this year than last. Will you get less money back from the IRS this tax season?

By Katelyn Washington Last updated

-

Four Things You Need to Know About Presidents Day and the IRS

Four Things You Need to Know About Presidents Day and the IRSTax Season The weeks surrounding Presidents Day are a particularly busy tax time for the IRS.

By Kelley R. Taylor Last updated